Creating an innovation mindset in your organisation

Five ways to begin…

What makes an organisation “innovative” and what can be done to help the people in it develop an innovation mindset? Well, what works for one organisation, may not work for another, and differences in internal and external constraints, tradition, reputation, budget, technical expertise and culture are just a few factors that can become barriers to innovation and progress. No matter the size or nature of an organisation, I believe that there are a number of practices that can help teams foster an innovation mindset, promote a willingness to be creative and implement positive change. This is a short guide or checklist if you like. It will help you outline where and when to innovate, who should be innovating, how innovation should be managed, the rules of engagement for innovation and finally what you should innovate. The benefits of this could be that you have a different view of your organisation, identify a competitive edge or you may find yourself in a more creative and enjoyable work environment. It’s a start to creating an innovation mindset, whatever the mission of your organisation.

1. Have you created your TAZ?

Where and when should you innovate? It sounds like good practice in an organisation to welcome team members to come to management any time with any ideas, but if this is your innovation strategy, you may be waiting for a long time. Innovation often doesn’t happen because we are busy and have our day jobs to do. Innovation is often an afterthought or something done at an away-day. Enter the idea of a TAZ. The idea comes from Anarchist philosopher Hakim Bey who wrote about a TAZ, a Temporary Autonomous Zone in 1985. A TAZ is a situation where creation happens. It must be out of every day (temporary), not controlled by anyone else (autonomous) and be in a specific time or place (zone). Think about a place or time where ideas flow for you. It could be when you’re out for a walk, during a run through the park, a hot shower or while you’re making tea in the morning, while everyone else is asleep. This creative time/space can be replicated in an organisation by making time for generating ideas. A Tuesday afternoon coffee and brainstorm at the same time each week, or a silent walking tour of a local area, followed by an ideation session will produce more good ideas than an open-ended request.

Bey wrote, “The TAZ is somewhere. It lies at the intersection of many forces, like some pagan power-spot at the junction of mysterious ley-lines, visible to the adept in seemingly unrelated bits of terrain, landscape, flows of air, water, animals.” Create your TAZ… bean bags and ping pong tables are optional.

2. Have you assembled an interdisciplinary team (and have you taught them how to challenge each other)?

Photo by Rose Elena on Unsplash

It seems obvious, but a group of single-subject experts can suppress innovation, creating a consensus that blocks out their decision-making process and gives an illusion of certainty. If we think we’re right and no one disagrees, we must be right. In a great TED Talk by Noreena Hertz, the economist notes that within a cluster of experts there will be a dominant perspective which will prevail and therefore prevent any descent or deviance. In an organisation this will also prevent innovation and creativity. Creating project teams from members of different parts of your organisation, or if it’s a very small organisation, making sure that there are significant differences among the members of the team is a good start.

It pays to hire people from different backgrounds, cultures, education and experience but if creating a culture of difference, it’s important to agree the terms on which those differences can be explored and challenged. Hyper Island have some great exercises in their Tool Box which can help a team create ways of working, and ways of challenging ideas from a position of care, not power.

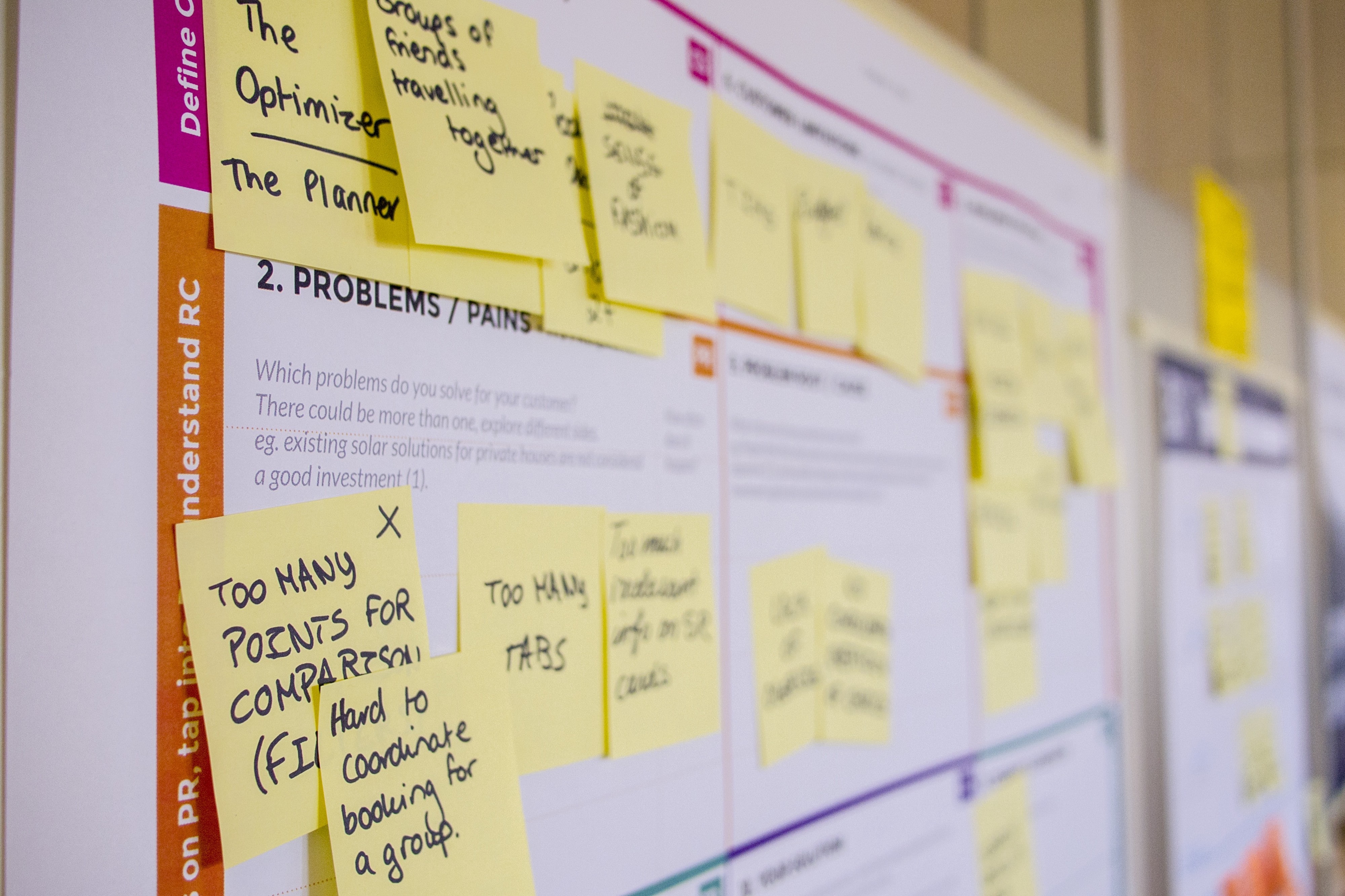

3. Are you facilitating ideation?

Photo by Daria Nepriakhina on Unsplash

Ideation needs to be managed. There are many ways to come up with ideas, from SCAMPER to PESTLE to good old-fashioned brainstorming, but it is not only about the method, but it’s also about the facilitation. In Paulus and Nijstad’s 2003 collection of essays called “Group Creativity”, they discuss that group brainstorming is often less effective than individual brainstorming. One reason for this is that in group situations we are more likely to search for similarities in each other’s ideas than differences, especially if we are unfamiliar with group members. Also, in traditional group ideation, only one idea can be presented at a time. Think about how you can encourage and facilitate individual ideation or pair ideation. Encourage people to build on each other’s ideas in group ideation and use technology to support the simultaneous input of ideas. Try this exercise from the Hyper Island Toolbox which asks team members to build on ideas by saying “yes, and…” instead of “yes, but…”

4. Does your organisation give permission to make mistakes?

Photo by Sarah Kilian on Unsplash

The fear of making mistakes can inhibit innovation and creativity, so it is important for organisations to foster a culture that doesn’t insist on getting it right every time. This idea of “fail fast, fail often”, however, is not about risking the collapse of an organisation on an idea, but about creating a culture where testing and prototyping are expected.

In a Forbes article last year, Dan Pontefract, CEO of the Pontefract Group cleared up this misconception.

“Originating from Silicon Valley and its ocean of start-ups, the real aim of “fail fast, fail often,” is not to fail, but to be iterative. To succeed, we must be open to failure — sure — but the intention is to ensure we are learning from our mistakes as we tweak, reset, and then redo if necessary.”

Being able to make mistakes is about creating and testing, allowing for failure and then creating something better from it. In an organisation, it’s about understanding what testing is and how a feedback loop can be put in place before a final outcome is then shared among the wider organisation and externally.

5. Are you looking to the future?

Photo by Lucrezia Carnelos on Unsplash

When you’re told to innovate, and you’re not sure where to start, think about the future, both methodically and imaginatively.

a) Do some horizon-scanning

In his work “The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility”, Marxist philosopher Franco “Biffo” Berardi discusses that, “the future does not emerge from pure fantasy nor from political will; it is inscribed in the present.” We don’t know the future, but we can see many possible “consecutive futures” by acknowledging what is happening now and multiplying its effect. If we keep polluting the sea, for example, it will be worse in the future. By understanding the past and what is happening now, this can be used to imagine future scenarios. Using future-mapping exercises, for example in Lucy Kimbell ’s Service Innovation Handbook can help a team visualise different futures and make plans for different eventualities.

b) Embrace uncertainty as an opportunity for innovation

The future will produce more fantastical scenarios than anyone can predict. Science fiction writer, Arthur C Clarke once commented,

“If by some miracle a prophet could describe the future exactly as it was going to take place, his predictions would sound so far-fetched, so absurd, that everyone would laugh him to scorn.”

Approach innovating for the future with awe and exaggeration. If you look at future uncertainty as purely risks to mitigate, you may be missing innovation opportunities. What would a utopian future for your organisation look like? What would a dystopian future look like? What can you do now to prepare for either of them?

Summary

Check-list:

- Have you created your TAZ?

- Have you assembled an interdisciplinary team (and have you taught them how to challenge each other)?

- Are you facilitating ideation?

- Have you got / give permission to make mistakes?

- Are you looking to the future?

So, you know where and when to innovation through your TAZ and you know who is innovating because you’ve assembled a crack interdisciplinary team. You understand that innovation needs to be facilitated well and that you need some rules about testing and iterating. Finally, if you’re not sure where to start innovating, innovate for the future.

Look out for further articles exploring each of these questions,and let me know your thoughts: hannah@alexander-wright.co.uk

Hannah Alexander-Wright, Innovation Consultant: www.alexander-wright.co.uk